The Camino de Santiago, Part 1

What is “The Camino”?

The Camino de Santiago, or “The Way of St. James,” is a network of medieval pilgrimage routes that span across Europe and lead to Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain. The most popular route is Camino Frances (in red on map), the trail usually referred to when you hear about “The Camino.” Camino Frances totals 500 miles long and traditionally begins in St. Jean Pied de Port, a town on the border of France & Spain.

The Camino’s history contains many layers, including the settlement in northern Spain by the ancient Celts and later by the Romans who constructed trade routes in this region. The pathway’s transformation into a pilgrimage route originates with the legend of the Apostle St. James.

According to the story, St. James had evangelized in Spain and then returned to Jerusalem where he was beheaded in 44 C.E. Afterwards, his remains were transported by boat back to Spain, either alone or with two of James’ disciples (depending on different versions of the legend). The boat landed along the coastal area of Galicia, and the bones were buried in a crypt.

As the legend goes, the bones lay forgotten until the 9th century when a hermit named Pelayo saw stars falling above the burial ground. He took it as a divine sign and told the local bishop, who then had the site excavated. The bones were unearthed & attributed to St. James. Subsequently, a church & a city named Santiago de Compostela became established in this spot. “Santiago” translates as “St. James”; the word “Compostela” as “field of the star,” which references the origin story & also a “cemetery” due to an ancient burial site found in this area.

Reports of miracles associated with St. James’ relics soon brought pilgrims to Santiago from across Europe. The city, along with Rome and Jerusalem, became a major pilgrimage destination during the Middle Ages.

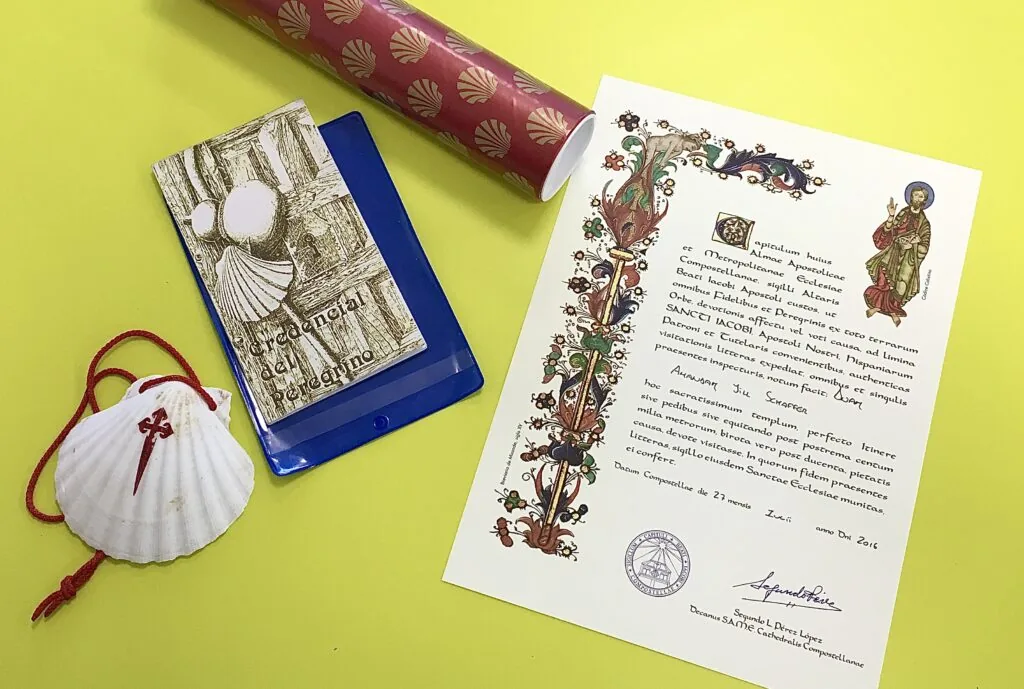

Over the centuries, the Camino endured cyclical periods of popularity. More recently, interest in the path has undergone a resurgence, and in 2024 there were over 499,000 walkers who received a Compostela, or certificate of completion. To aquire a Compostela, a pilgrim needs to trek at least the last 100 kilometers (62 miles) or bike 200 kilometers into Santiago de Compostela.

Visual imagery of St. James as a “peregrino” is common along the Camino. He is identified by his attributes — hat with shell, cloak, walking stick with gourd, & a “pilgrim pouch.”

People of all ages walk the Camino and come from places world-wide, although many pilgrims are from Spain and other countries in Europe. Some people walk with family, friends, or a group, while others go solo and may meet walking partners along The Way. Pilgrims often form communities of fellow walkers while on the ‘Road,’ and these friendships can be an integral part of the Camino journey.

Other Camino routes:

Besides Camino Frances, there are 8 other main routes plus more trails that are less traveled. For maps and info about routes check out The Confraternity of St. James & Gronze.com (translate in Google). In 2024 the most walked paths besides the Frances included Camino Portuguese (in Portugal/Spain), Camino Ingles (north of Santiago in Galicia), Camino del Norte (along the northern coast), and Camino Primitivo, a trail known as “The Original Way” because of its status as the first established route in the 9th c. Additionally, there are 4 main French routes that merge with Camino Frances — starting points for these are in Paris, Vézelay, Le Puy-en-Velay, & Arles.

Once arrived in Santiago, some walkers choose to trek Camino Finisterre onward to the coastal towns of Muxía & Finisterre, or “Land’s End,” where the ancients thought the earth ended. Muxía is the destination in September of a “romeria,” an annual short distance pilgrimage that includes a procession to the Virgen de la Barca (Virgin of the Boat) shrine by the water’s edge. Similar to the Compostela, there are certificates for walking to Finisterre (a Finisterrana) & Muxía (a Muxiana).

The medieval bridge in Ponte Maceira on Camino Finisterre

Why is a shell the symbol of the Camino?

During the Middle Ages cockle shells became associated with the Camino. One explanation why involves a story connected to the legend of St. James. As the boat carrying his remains sailed along the coast in Galicia, a young bridegroom on horseback followed it. The horse became spooked and fell into the ocean with the man; both miraculously survived and rose out of the sea covered with shells.

Other connections between shells and the Camino include their availability on the coast — medieval pilgrims might have used shells for drinking and eating or brought them back home as proof of their journeys. In addition, during the Middle Ages large shells were given as Compostelas and sold as mementos at markets by the Santiago Cathedral. Pilgrims also attached shells onto their hats or clothes.

Thus, over time a shell became the symbol of the Camino, and images of it can be seen on art, architecture, & trail markers along the routes. It’s said that on some markers the shell’s ‘ribs’ represent all the routes, and these lines converge at the end of the shell to point towards Santiago. In more recent history, walkers attach shells onto their backpacks at the beginning of their journeys to designate themselves as Camino pilgrims. Walkers’ shells often include the Cross of St. James painted on them, which was the emblem of the Order of St. James, a military organization formed in the 12th c. that protected pilgrims.

Why do people walk the Camino?

There is a variety of reasons that people are ‘called’ to trek the Camino. Some walkers go for religious/spiritual beliefs while others are inspired after seeing a film or reading a book about the Camino. Other pilgrims are going through a transitional period or crossroads in life (such as a career change or retirement) or walk in memory of loved ones who have passed. People also walk the Camino to explore the route’s history and the art & architecture connected to it.

Some go as a celebration and thanksgiving (for an anniversary, physical recovery, etc.) or are following in the footsteps of family/friends who walked a pilgrimage in the past. Others are drawn to the idea of a big adventure or perhaps to undertake the physical test of a long hiking journey. And for some walkers it’s being in nature or engaging with Spanish culture.

All pilgrims have their own unique stories to tell of why the Camino resonates with them — it might even be a combination of reasons, or the original purpose may change after they’ve begun the trek. The Camino offers walkers the time and space to reassess, refresh, and meditate about their lives. For many people the pilgrimage experience is both an external, or physical, challenge, and also an internal, or contemplative, journey.

Medieval pilgrimage:

Pilgrims during the Middle Ages walked the Camino primarily for religious purposes. They sought to gain indulgences or pardons from “sins” by undertaking the long journey to Santiago de Compostela. Some people, however, had to walk a penitential pilgrimage — ‘wrong doers’ were sentenced to an arduous trek because of crimes committed. For other people, walking to Santiago was an adventure & an opportunity to explore beyond their village.

Additionally, there were pilgrims who made a vow to walk the Camino to express gratitude for ‘miracles’ that had happened, or they sought physical healing “from the heavens” by visiting St. James’ tomb to ask for miracles through the saint’s intercession. At the Cathedral, pilgrims participated in prayer vigils and presented candles, oil, or ex-votos as offerings.

Ex-votos (Latin for “from a vow”) were figures or anatomical forms cast mainly in beeswax. They were believed to be thaumaturgical, or miraculous, and often replicated body parts that needed mending. Small, medium, and even life-size ex-voto forms were produced. Pilgrims purchased them at sacred sites from merchants, apothecaries, or church shops.

The ex-voto tradition can still be found in Spain, including in Muxía where these objects are left by pilgrims as part of the town’s annual romeria. The photo shows a modern day ex-voto figure by the Colegiata de Sar church in Santiago — the yellow color indicates its beeswax content.

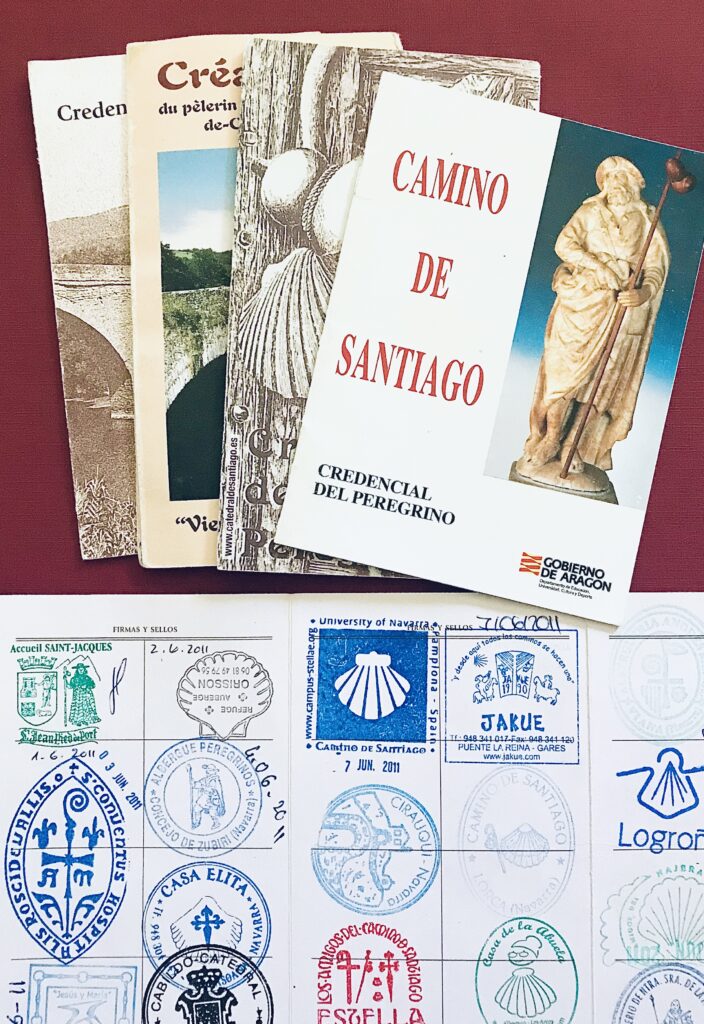

Camino credentials & sellos:

To record Camino journeys, walkers carry with them credencials (‘Pilgrim Passports’) and get sellos (stamps) along the route; digital credencials are also now available for collecting sellos. Credencials are required in order to stay at albergues (walker hostels). In Santiago walkers then present credencials at the Pilgrim’s Office to acquire the Compostela certificate. This document originated in the 14th c. and is in Latin; walker’s names (in Latin) and the date are written down when receiving a copy.

In 2021 the Pilgrim’s Office implemented a “Pilgrim Registry” to help award Compostelas. Read more about the registry and credencial app under Camino tips & misc. in Camino Resources, Part 2. Below is information regarding the paper credencial, which is typically an accordion-style booklet and 6.25″ x 3.75″ when folded up:

- Credencials can be purchased for 2-3 Euros at pilgrim offices, churches, & municipal albergues run by regional Camino organizations.

- In the U.S. credencials are available from the American Pilgrims on the Camino (no membership fee needed but a donation is suggested). They can also be bought from the Camino de Santiago forum store, Casa Ivar (shipped from Spain) or The Confraternity of St. James (shipped from England).

- More than one credencial booklet likely will be needed if a walker is on the trail for many weeks.

- Most credencials don’t include a protective envelope/sleeve; consider bringing one with to minimize wear & tear.

- Sellos are given at albergues when walkers register for the night. They’re also available at churches, bars & restaurants, historical buildings, etc.

- Each sello is unique & often includes the name of the place/town where it was received.

- For the last 100 kilometers into Santiago it’s required to get at least two sellos per day as proof of walking in order to receive the Compostela (needed for the app too).

In addition to the Compostela, there are two other certificate options that walkers can receive when presenting their credencials at the Pilgrim’s Office. One is a document called a Certificate of Welcome, which is a secular version of the Compostela; the other is a Certificate of Distance that has been available since 2014 (for 3 Euros). This document records the number of kilometers walked or cycled, the starting point, and date of arrival to Santiago. Some walkers get this certificate in addition to the Compostela as a keepsake of their journey.

The Compostela on a table at the Pilgrim’s Office; “tubos” to store the document are available there too.